Growing up, we had an attic stretching the length of the house. When spring-cleaning was forcibly enforced, we three girls would take all of the things we could not bear to part with, virtually everything, up to some corner in the attic.

When my poor mother finally got ready to downsize, she logically assumed we would return for all the treasures she housed patiently for us through the years. But no. We wanted all of those things – my Shirley Temple doll and Barbies and those hoop-skirted formals of my oldest sister – but we wanted them in my mother’s house, not ours.

We are now going through mountains of papers, books and photos carefully retained for more than a century by the Mister’s side of the family. Our generation now is supposed to assume guardianship, but, in our case, we already have downsized. The next generation has not yet, if they ever so choose, upsized.

I am the last person who should ever go through remnants from the past. I cherish every scrap of paper offering clues about past lives. I wander through old photos more slowly than Moses found his way out of the desert.

Take this Bible, for example.

It’s older than Methuselah. Okay, not quite that old. It was published in Philadelphia in 1831.

This is not your ordinary King James I Bible. In addition to the Old and New Testaments, it ecumenically includes the Apocrypha, all translated out of the original tongues. There are “marginal” notes and references; an alphabetical index of every character mentioned; tables of scripture weights, measures and coin; historical maps; and numerous engravings. The cover is gold-embossed, and the Florentine lining almost makes our granite countertop seem pale. It dates from a time when historical engravings could even bare breasts.

Of course all of these things add up. They add up to a full four-inch-thick volume, rather weighty to slip subtly onto any bookshelf.

The original owner bore a name from one of the most brutal fire-and-brimstone books of the Old Testament, Zephaniah. This book describes a vengeful god making men plant vineyards, but not allowing them to drink a drop of the wine they produce (Chapter 1: Verse 13). The Lord in this book was fierce:

I will consume man and beast; I will consume the fowls of the heaven, and the fishes of the sea, and the stumbling-blocks with the wicked; and I will cut off man from off the land, saith the Lord.

(Chapter 1, Verse 3)

Reading that made me worry that the Mister’s third great-grandfather might have been rather frightening. But Zephaniah Turner Conner (1807-1866) appears to have been named after his Aunt Sallie’s husband, Zephaniah Turner (1779-1855). Zephaniah Conner and his wife Louisa Ann Godwin (1815-1891) were descended from families who’d been in Virginia for several generations, but the newlyweds headed out to Macon, Georgia, after their marriage and increased the population there by producing at least 11 children, according to their Bible. Among the great family names bestowed upon these children is a personal favorite, Granville Cowper Conner (1837-1900).

Although Zephaniah Conner served as a colonel in the Civil War, he allowed his daughter Virginia (1839-1931), the Mister’s second great-grandmother, to marry a man born in Massachusetts. Serving as a Lieutenant in the Georgia cavalry easily made up for the original birthplace of William Allis Hopson (1836-1873). The couple took their vows in Christ Church in Macon, Georgia, in 1866. The Bible, with a ticket from the 1871 Georgia State Fair serving as a bookmark, was handed down to them.

Their daughter Georgia Hopson (1870-1928) married Lucius Mirabeau Lamar, Jr. (1866-1931), a family with a set of remarkable names as well, in Christ Church in 1894 before heading to Mexico. Perhaps she lugged the weighty Bible with her on that rugged journey.

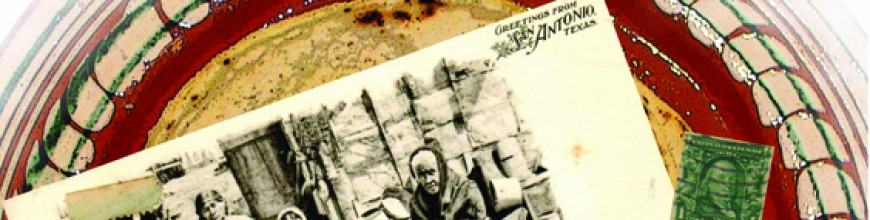

The Bible then found its way to San Antonio to the home of the Mister’s maternal grandmother, Virginia Lamar Hornor (1895-1988).

And now the Family Records contained in this tome covering half my desk when open taunt me to dig deeper into all of their backgrounds. Some day I will, but I have a whole cemetery of people whose memories I currently am excavating.

I am closing the cover now, wondering who will assume the role as its caregiver. Maybe this Bible that has traveled so far needs to find its way back to Macon.